John Andrews was Australia's first internationally famous architect - before Glenn Murcutt. His work is generally considered to have characteristics of late International and Brutalist Styles. Andrews significant early work is in North America, where he practiced after moving for graduate study at Harvard, and includes Scarborough College in Toronto (1965), Miami Seaport Passenger Terminal (1970), the architecture studios at Harvard, Gund Hall (1972), and the Canadian National Tower (1975).

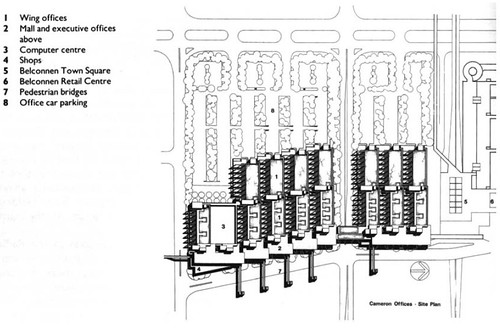

He was enticed back to Australia by the National Capital Development Commission (NCDC) to design the Cameron Offices, which at that point was to be the largest office complex ever built in Australia and the keystone development of the new satellite city Belconnen. The NCDC had proposed towers, but Andrews says he accepted the commission only on the condition that they be a low rise complex that allowed courtyard gardens and plenty of natural light.

The Australian Institute of Architects (AIA) Citation acknowledges the Cameron Offices as "Canberra's, and it appears Australia's, first and possibly only true architectural example of 'Structuralism' where buildings are integral and contributing elements of an overall urban order rather than separate and individual elements."

|

| Site Plan from 'Australian Architecture Since 1960', 2nd Edition, 1990, Jennifer Taylor, Page 106 |

The Cameron Offices are also notable for their expressed structure, raw materiality, strong shapes and bold composition.

Brutalism is a rather unfortunate term. It was coined by Alison and Peter Smithson from the French term for raw concrete to describe an attitude to materiality. The public has been able to use the term popularly to disparage all architecture of this period - often associating it with concrete use that is cold and oppressive, and misguided social planning such as government housing complexes that became ghettos.

The best Brutalist architects such as John Andrews, Col Madigan and Le Corbusier soften their use of concrete with juxtaposition against other materials, landscape and particularly with use of light and spatial arrangement.

So why were the Cameron Offices not liked? The public never understood or even engaged with them because they were removed from their urban context, isolated. Workers had mixed experiences - many appreciated the generous natural light and views to gardens. Others remember that the rooftop gardens and rooftop tennis courts were notorious for leaks and that the courtyard gardens could become wind tunnels. The buildings later life was undermined by neglect, particularly of the gardens, and the public's general apathy toward Brutalism. Further, the circulation made it difficult for contemporary tenants with no centralised reception or security and no disability access.

After the Federal Government sold the Cameron Offices, John Andrews was involved in investigations to retrofit the buildings as boutique residential apartments, however the new owners determined that it would be cheaper to demolish them.

The AIA and others made attempts to save them, but demolition proceeded before heritage assessment processes had been finalised, with general support from the public. Why was the masterpiece of one of Australia's most significant architects not appreciated? John Andrews won the AIA Gold Medal in 1980 and the Cameron Offices is one of only 10 Australian buildings recognised on the International Union of Architects' (UIA) World Register of Twentieth Century Architectural Heritage.

John Andrews bravely took a student group from the University of Canberra to look at the Cameron Offices in mid 2007 when only the first two wings had been demolished. He was clearly upset at seeing the neglected state of the buildings and avoided looking at the demolished side, but was heartened as dusk settled and the Cameron Offices with lighting looked as elegant as ever.

This post has been written to contextualise the development of a light projection art installation project that will hopefully use the remaining wings of the Cameron Offices as site. This project is an opportunity to encourage a new public engagement with the building, which perhaps has even more cultural interest as a legacy of its misunderstood and unappreciated past.

Update - also this article and particularly the comments following it are of interest as they demonstrate how public appreciation of architecture can easily be changed